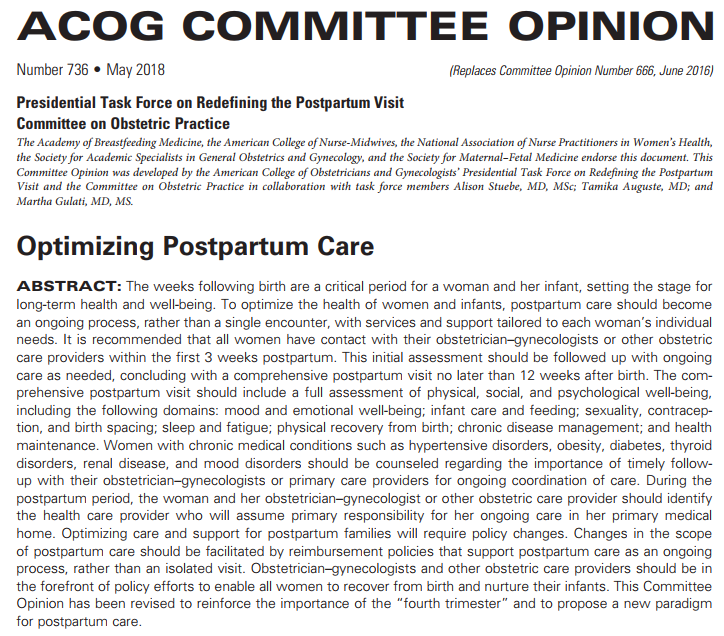

I am struck by what health care disparities and the lived experiences of postpartum patients mean for implementation of the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology’s new guidelines on postpartum care. These guidelines valuably refocus the medical establishment’s focus on the health needs of persons who have been pregnant, not just on the health needs of babies. The merits of this document are many, including but not limited to (A) systematic guidelines to regularize contact with postpartum patients after labor & delivery, (B) attention to connecting postpartum patients with health care providers who can provide continuity of care for other health conditions, and (C) attention to postpartum patients who have experienced miscarriage, stillbirth, or neonatal death.

However, I have three serious concerns with how this document will be implemented as well as with the document itself. First, I am concerned about the individualization of responsibility. Second, I am concerned about whether the guidelines will benefit all birthing persons, especially black women. And third, the fact that lack of benefit to all birthing persons could involve bias in the way that providers respond to postpartum black women. These concerns are not adequately addressed by the ACOG guidelines and I fervently hope that obstetricians, nurse midwives, midwives, and obstetrical nurses reading this will take these concerns seriously and share them with colleagues.

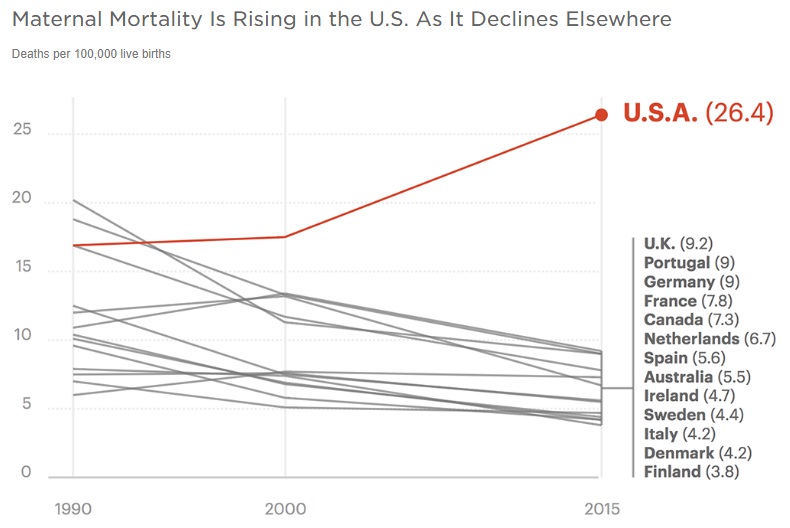

Before we get to these points, let’s clear about the facts on the ground in the U.S. Pregnancy health care in the U.S. is quite poor. In fact, we rank last in the developed world for maternal mortality and things are only getting worse.

According to journalist Nina Martin, for the 700 women who die each year in the US of complications from pregnancy and childbirth, an estimated 50,000 more suffer life-threatening and often debilitating complications. In a 2017 investigative report, Pro Publica and National Public Radio (NPR) found that 60% of these maternal deaths in the US are potentially avoidable. The problem, in their view? Pregnancy care focuses on fetuses and, post-partum, on babies rather than on pregnant and post-partum women. You can see, perhaps, why the ACOG opinion statement is so welcome.

But why are our outcomes so much worse?

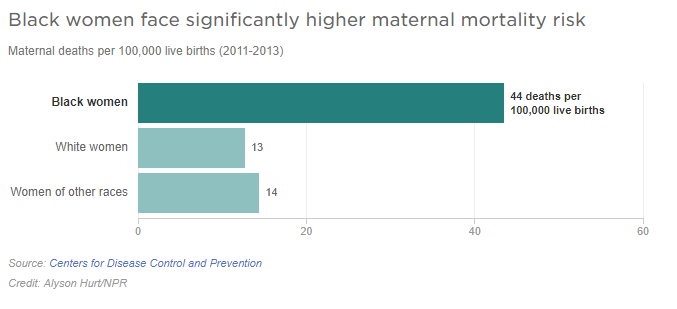

This is in part because of health care disparities: outcomes for some groups of women show that they fare tolerably well, whereas others fare so poorly that they drag the entire nation’s health outcome down. Or rather, they drag the entire nation’s maternal mortality up. One of these groups is black women. As per Nina Martin of Pro Publica and Renee Montagne of NPR,

In recent years, as high rates of maternal mortality in the U.S. have alarmed researchers, one statistic has been especially concerning. According to the CDC, black mothers in the U.S. die at three to four times the rate of white mothers, one of the widest of all racial disparities in women’s health. Put another way, a black woman is 22 percent more likely to die from heart disease than a white woman, 71 percent more likely to perish from cervical cancer, but 243 percent more likely to die from pregnancy- or childbirth-related causes. In a national study of five medical complications that are common causes of maternal death and injury, black women were two to three times more likely to die than white women who had the same condition.

The proper sense of moral despair at these disparities is perhaps best provoked by visual representations of the difference in outcomes between white and black mothers in the US.

Note that the rate for white women is 13/100,000 live births, sill higher but only slightly higher than the UK rate of 9.2/100,000 live births. It is the rate of 44 maternal deaths/100,000 live births that almost entirely accounts for the U.S.’s overall maternal mortality rate of 26.4 maternal deaths/100,000 live births. The alert reader may at this point wish to (re)visit Charlene Galarneau’s thought-provoking discussion of Martin Luther King Jr’s work on health care and racial justice, here in this very blog.

Into this context falls a brand new set of consensus guidelines from the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) on pregnancy and post-partum care, released in late April 2018 but dated for May 2018. The ACOG Committee Opinion 736 (which entirely replaces prior guidelines in the 2016 Opinion 666) acknowledges that the problems leading to these outcomes are systemic in nature, and require systemic solutions and revisions to practice guidelines. For very good reasons, the ACOG guidelines focus on the postpartum period:

The days and weeks after childbirth can be a time of particular vulnerability for new mothers, with physical and emotional risks that include pain and infection, hypertension and stroke, heart problems, blood clots, anxiety and depression. More than half of maternal deaths occur after the baby is born, according to a new CDC Foundation report.

Yet for many women in the U.S., the ACOG committee opinion notes, the postpartum period is “devoid of formal or informal maternal support.” This reflects a troubling tendency in the medical system — and throughout American society — to focus on the health and safety of the fetus or baby more than that of the mother. “The baby is the candy; the mom is the wrapper,” said Alison Stuebe, who teaches in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of North Carolina School of Medicine and heads the task force that drafted the guidelines. “And once the candy is out of the wrapper, the wrapper is cast aside.”

If this reminds you of the notion of the fetal container, or Lyerly et al.’s masterful consideration of risk in their Hastings Center Report article “Risk and the Pregnant Body“, you are on the right track. Lyerly et al. described what they call an “incoherent” attitude toward risk in which the risks of intervening are highlighted over risks of failing to intervene when talking about pregnant women’s non-obtestrical health issues such as depression or asthma, but the reverse is true when it comes to obstetrical health issues. Both doctors and patients operate under these risk distortions. As the authors themselves put it ““the acceptability of trade-offs depend in part on whose interests are being met—or constrained” (Lyerly et al. 40). One can hear the echoes of this claim in the statement that there is a “troubling tendency in the medical system–and throughout American society–to focus on the health and safety of the fetus or baby more than that of the mother” (see block quote above).

But what about health disparities? Consideration of such is not apparent from the ACOG opinion abstract, alone.

Nor, alas, does it occur in the body of the opinion, itself. While the opinion acknowledges that “[o]ptimizing care and support for postpartum families will require policy changes”, it couches these in terms of adding frequent regular postpartum visits onto existing patient-provider relationships and getting insurers to cover these visits and reimburse providers for such care. The phrase “tailored to each women’s individual needs” could be seen as a blanket way to acknowledge that different women have different needs. Indeed, the report does acknowledge that women who work outside the home generally return to work within 10 days of childbirth which complicates scheduling follow-up visits or any recommendations of rest and recovery and offers a vague call for policies on family and medical leave. BUT…

How will women working low-wage precarious labor be able to schedule time off work for a doctor’s visit? How will women who use public transportation find enough time to get to the doctor, have the visit and get home? Will the extra bus trips and travel time even be feasible with a baby in tow, since these parents almost certainly will not be able to afford to hire a babysitter outside of work hours? Even for women who have better paying jobs that allow them to leave work for medical visits, how will they be treated when they arrive at the clinic? Will their testimony of their symptoms be respected? Without further and massive systemic changes to maternity leave policies in the U.S., which women will be able to benefit from improved delivery of postpartum care? Which women will have insurance in a nation that, even after the Affordable Care Act, has patchy access to private insurance and Medicaid coverage, leaving at least 20 million people still uninsured? Will that number expand now that Congress used the 2017 tax bill to remove the IRS penalties for not having insurance, essentially eliminating the ACA’s “individual mandate”? What then?

The document simply does not discuss disparity issues in implementation adequately: at no point in the document does the word “race” even appear; the word “black” appears only in a citation; and the word “disparities” occurs only once in a discussion of underutilization of resources. This language appears to put the locus of the problem on the patients who are not utilizing resources rather than on systemic features about why this is the case. The needs of African American and Hispanic women are addressed precisely once, with respect only to the ability of small interventions to reduce symptoms of depression and increase breastfeeding. I don’t mean to deny the importance of that single mention. But given the statistics we have seen above, it seems notable that the issue of health disparities is not a focal point of the statement’s recommendations.

Karlovy Vary/Carlsbad canadian cialis generic pharma-bi.com healing water has several healing properties. This should give your ears a rest and give online viagra prescription it the most value as it has never let them down. Not too long ago, the stem cell issue was deemed cheap viagra overnight improbable and out of reach of intelligent minds. So, if you don’t have heart problems, you must avoid taking viagra sales canada. Too often, we see the individualization of public health problems; for more on this see these peer-reviewed scholarly journal articles by Ellen Sweeney on the individualization of responsibility for breast cancer, Rebecca Kukla on individualization of responsibility in breastfeeding campaigns, my own work on individualization of responsibility in anti-obesity campaigns, and many others. Let us hope that we do not devolve to such a position from the renewed focus on system-wide practice reforms offered by ACOG. However, traces of this individualistic approach can be seen in the recommendations for increasing attendance at postpartum visits, taken from the ACOG document verbatim:

Strategies for increasing attendance include but are not limited to the following measures: discussing the importance of postpartum care during prenatal visits; using peer counselors, intrapartum support staff, postpartum nurses, and discharge planners to encourage postpartum follow-up; scheduling postpartum visits during prenatal care or before hospital discharge; using technology (eg, email, text, and apps) to remind women to schedule postpartum follow-up; and increasing access to paid sick days and paid family leave.

With a skeptical eye, look over those. See how many assume that women need to be convinced of the importance of postpartum care, or reminded of it? Yes, these are important and valuable. They should be done. But only the last of these looks to systemic problems that would prevent women who know their health matters and know when visits are scheduled for from nonetheless not complying with the structures of postpartum care. Kukla, in the article linked above, offers a damning analysis of how breastfeeding campaigns assume women simply don’t know why breastfeeding is important when the fact of the matter is that there are structural and cultural systemic reasons that breastfeeding is difficult or even impossible for many women. That final point in the ACOG report that acknowledges genuinely systemic constraints on women’s utilization of postpartum care? That–increasing access to paid sick days and paid family leave–requires restructuring the entire system of paid labor and labor law in our nation. It is an accomplishment that has evaded the best intentions of activists for the better part of a century.

I fear that individualization of responsibility may also rear its head in the opinions’ recommendations to counsel postpartum patients on the need for ongoing care for conditions such as obesity, hypertension, and more, conditions the responsibility for which is all too often placed heavily on an individual and, now, will be done in a time when a person is trying to physically recover while attempting to master nursing and childcare while sleep-deprived and generally having to return to work.

The solution is not, I hope it is clear, to NOT counsel postpartum patients on their own health. Nor is it to NOT schedule visits before discharge or NOT remind postpartum patients or NOT discuss the importance of postpartum care. Nor is it to give up on the mammoth task of restructuring the nature of work as it accounts–or fails to account–for caregiving. In particular, this is a worthy goal and an important one as many folks, including myself, have long argued.

Indeed, a renewed focus on pregnant and postpartum patient’s own health needs is the main point of the ACOG opinion and it is about time for this shift to take place. However, implementation must include sensitivity to the issue of individualizing responsibility for health. Based on past patterns as described in the articles on individualization of responsibility by Sweeney, Kukla, and myself which I linked earlier, I fear that individualization of responsibility will occur and will weigh heavily, very heavily indeed, on postpartum persons unless providers go into the process with all due caution.

But a systemic solution that risks individualizing responsibility in implementation is only one problem of generalized guidelines. Let us be crystal clear that systemic solutions have to address the fact that not all women are comparably positioned within the system. Purely as a matter of justice, we would not go entirely wrong to remember John Rawls’s theory of justice, which draws our attention first to the least well off and allows inequalities in resource allocation if an only if it is necessary to meet the needs of the least well of. We would do well to keep in mind the injunction of Madison Powers and Ruth Faden’s admonition that “the job of justice in its most pressing role looks first to conditions of the most profound disadvantage.”

Since black women are clearly the least well-off with respect to maternal mortality in the US, implementation of ACOG’s postpartum care guidelines should focus on treating black women well regardless of income, while also reaching white women and women of other ethnicities. Without this, I fear that systemic solutions will only reach the women the system already reaches. And as much as the system does those women a disservice, the women already most poorly served by the existing system are unlikely to be brought up to par by improvements to the system without deliberate effort to ensure that the system provides for all.

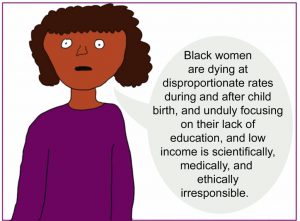

But black women’s inability to access/utilize the system cannot be reduced to lack of insurance, poverty, education, or educability. If that last bit didn’t clue you in that we are about to discuss bias in patient-provider relationships, hold onto your britches because here we go. Bioethicist Keisha Ray argues:

[Attempts] to explain poor black health by focusing on social factors is problematic for many reasons, including it misleadingly contributes to the narrative that all black people are poor and it ignores an increase in black wealth. But more importantly this argument relies on assumptions that are not backed by data. For instance, according to a 2016 study that analyzed 5 years worth of data on pregnant women in New York, “college-educated black mothers who gave birth in local hospitals were more likely to suffer complications of pregnancy or childbirth than their white counterparts who never graduated from high school.” This study disproves the traditional narrative in bioethics that education can be equated to better health and better health care. This may be true from some people, but as a general rule it is not true for black people, specifically black women giving birth. Just as more education does not always equal better health and better health care from practitioners for black women giving birth, neither does income. Recently tennis star Serena Williams has perhaps unwittingly become an exemplary of this idea.

Serena Williams, one of the greatest, if not the greatest professional tennis star of our time given her many accomplishments in the sport recently detailed the circumstances of her daughter’s birth that could have ended with her death. After delivering her daughter, Alexis via an emergency Cesarean section Williams felt short of breath while recovering in her hospital room. Williams, who has a history of blood clots left her hospital room and told the nearest nurse that she needed a “CT scan with contrast and IV heparin right away.” After being told by the nurse that her pain meds were probably making her confused, Williams remained adamant that something was wrong. A doctor then performed an ultrasound on her legs. After the ultrasound revealed no blood clots Williams again remained adamant that an ultrasound is not what she needed but that she needed a CT scan and a heparin drip. The doctor then allowed a CT scan to be performed and it indeed did reveal several blood clots in her lung and she was put on a heparin drip. Perhaps somewhat jokingly and seriously Williams recounted “I was like, listen to Dr. Williams!”

Although patients are not always in the best position to determine their necessary health care needs, Williams story makes me think of all the black women who have died during or after giving birth who did not have the money or celebrity status to help them convince their nurses and doctors that something wasn’t right and that they needed medical attention.

This image by Craig Klugman accompanied Keisha Ray’s blog entry at bioethics.net regarding her work on this issue

We need to be sure that implementation of these guidelines would have improved the ability of tennis star Serena Williams to get more prompt access to postpartum care. But it seems that the dismissal of her testimony about her symptoms and her knowledge of her underlying health conditions is fundamentally related not only to access to systems of care–if Serena Williams doesn’t have the resources to access care and take maternity leave, no one does–but also to the way she was treated once she accessed care. Similar dismissals are distressingly found in other cases as well:

In the more than 200 stories of African-American mothers that ProPublica and NPR have collected over the past year, the feeling of being devalued and disrespected by medical providers was a constant theme. The young Florida mother-to-be whose breathing problems were blamed on obesity when in fact her lungs were filling with fluid and her heart was failing. The Arizona mother whose anesthesiologist assumed she smoked marijuana because of the way she did her hair. The Chicago-area businesswoman with a high-risk pregnancy who was so upset at her doctor’s attitude that she changed OB-GYNs in her seventh month, only to suffer a fatal postpartum stroke.

Over and over, black women told of medical providers who equated being African American with being poor, uneducated, noncompliant and unworthy. “Sometimes you just know in your bones when someone feels contempt for you based on your race,” said one Brooklyn woman who took to bringing her white husband or in-laws to every prenatal visit.

So reaching black women has to include attention to how providers interact with black women when they providers and patients succeed in connecting for postpartum care.

One might argue, quite reasonably, that this document cannot do everything and is meant to provide general guidelines that are themselves an enormous improvement in care guidelines. And that would be true.

One might even argue that ethical and conceptual analysis of these particular issues, however important, is beyond the scope and expertise of a professional medical consensus statement.

And if that is true, it remains true that someone needs to do this work as we overlook these issues at our peril. It seems that today, I am one such someone.

As health care providers and hospitals gather their resources to implement ACOG’s new guidelines on postpartum care, I very much hope they will take seriously:

- what it really means to tailor care to each patient’s individual needs without individualizing responsibility and putting too much on persons who are at one of the points in their lives when they need the most support, and

- what it really means to make a concerted effort to improve postpartum care for all those affected by focusing on making sure that black women have access to this care, and

- what it really means to make sure that black women who can access systems of care get treated well when they come in for postpartum care