Two studies which have recently hit the press reinforce a problem I have been considering for some time, namely the difficulties which transgender persons face in getting care. Herein, I will give an overview of these difficulties, the new studies, what they reveal about causes of provider’s behavior with respect to trans persons, and some brief recommendations for how providers can do better.

Transgender health advocates Sabrina Suico of the Couples Health Intervention Project and Brionna of the Mariposa project both work with services dedicated to improving the lives of transgender or gender-variant people of color. Image Credit: Aubrie Abeno, via mintpressnews.com

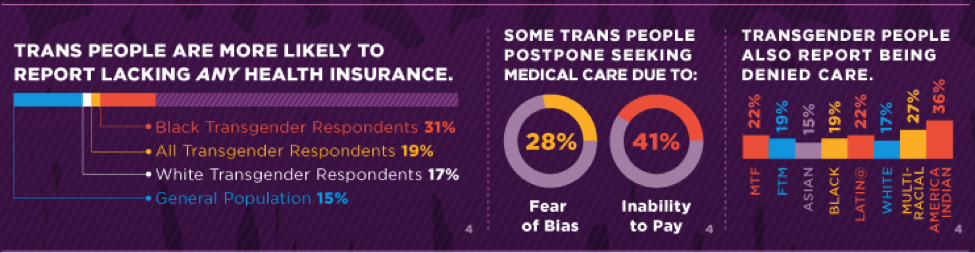

In 2012, I presented a paper at the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities, “She Walked Out of the Room And Never Came Back…”, in which I discussed the case of a patient who had been denied care by health care personnel while visiting the ER for a broken limb before finally being seen by another provider. The first provider walked out in a huff after the transgender patient’s trans status became clear as the patient’s anatomy was revealed during a diagnostic procedure. After leaving the patient alone, in pain, with no idea whether to leave and go to another facility or wait, another provider came into the room and professionally and compassionately provided the necessary medical care. This, I found, was not uncommon. Approximately 1 in 5 transgender patients have put off preventive medical care due to experiencing, or fear of experiencing, discriminatory behavior directed at the patient by clinical staff. According to some figures, this rises above 1 in 4 (28%), and transgender persons report being denied care across every demographic but worst for transgender women, who were assigned male sex at birth, than for transgender men who were assigned female sex at birth. The fact that transgender persons experience difficulties with access to health care should come as no surprise. In 2011, the Institute of Medicine released a report which addressed the many ways in which poor access to basic medical care for transgender individuals is “due largely to social stigma” and “fear of discrimination in health care settings” as well as lack of employer-provided health insurance due to employment discrimination.

In my paper, I argued—and still believe—that the ability of providers to treat any patient in ways that render the patient untrusting of health care providers in general indicates serious problems with patient-provider relationships in general. This is the case whether the patient is transgender, a person of color, of a socioeconomic class or profession which has low social status, has body piercings and tattoos, or any other condition that leads the provider to treat the person seeking medical assistance as something other than a proper patient. For transgender patients, the risk of being discriminated against by health care providers is, in principle, higher than being discriminated against by the average citizen. After all, providers are more likely to have privileged access to the bodies and medical histories of transgender persons which may reveal that the patient’s gender is at odds with societal expectations for the sex the patient was assigned at birth. That is precisely what happened to the patient with the broken limb in the case, above.

In late 2012, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services rendered an opinion on Section 1557 of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, indicating that this sort of discrimination is prohibited in any clinical setting receiving Medicare or Medicaid funding. One example of such treatment is a patient who was not treated for a deviated septum because of her trans status. However, patients who experience it must be willing to file a complaint against the provider and institution. This risks outing them further, a dangerous situation for transgender persons who are not fully protected from employment discrimination and are very much more likely than the general population to have attempted suicide, suffered employment discrimination or other loss of economic opportunity, and experienced homelessness.

Several recent studies related to this topic hit the news March 12 and 13 of 2014. One study out of Wayne State University’s School of Social Work (in Detroit) reinforces the finding that poor treatment of transgender persons in clinical medical settings is a common problem. Researchers used data from the 2008-2009 National Transgender Discrimination Survey—NB: prior to the passage, much less the on-going implementation of, the Affordable Care Act—to show that 41% of the 1,711 transgender men surveyed in fact reported being “denied or refused care, verbally harassed, or physically assaulted in a doctor’s office or hospital.” The researchers acknowledge that a limitation of culling this survey for evidence is that other questions were not asked: was the harassment or assault perpetrated by clinic staff, and if so by what types of personnel? However, the issue of being denied or refused care clearly originates with clinic staff.

Another study which just hit the news is out of Canada’s Western University. Researchers there interviewed 408 transgender people in Ontario, revealing that more than 20% (1 in 5, a number which we saw earlier) report they have avoided the emergency department in a potential medical emergency because they feared suffering negative consequences. Note: the negative consequences they feared suffering were at the hands of providers, and outweighed the negative consequences they feared suffering from lack of treatment. This issue of refusing to seek emergency care is different from the 1 in 5 figure given earlier, which pertained to putting of preventive medical care due to fear of stigma. The same study also found that 32 percent of study participants reported experiencing “hurtful or insulting language” and 31 percent were told “the healthcare provider didn’t know enough to give them care.” In addition, 52% reported trans-specific negative experiences in the ER. That’s not fear of stigma. That’s actual stigma. The data came from a longstanding research project called Trans PULSE.

Note that none of the kinds of discrimination I have discussed have to do with transgender persons’ access to hormone therapies, sex reassignment surgery, or other procedures related to their trans status (the issue of whether it is ethical to claim conscientious objection in refusal to treat conditions related to trans status is a separate, and unsettled, question). Rather, the treatment in question is for what I call care unrelated to trans status: broken limbs, pneumonia, injuries, colds, PAP smears, prostate exams, and other forms of acute and preventive care which both transgender and non-transgender persons may require.

It seems we have two sources of negative encounters between transgender persons and clinical providers. First, stigma and negative attitudes pertaining to transgender lead some providers to be disrespectful or actively hostile to transgender patient. And second, providers’ lack of knowledge about transgender leads them to believe they cannot responsibly treat transgender patients even for care unrelated to trans status. It is often not the case that a person’s trans status will complicate care for the problem with which they are presenting, and it may be inappropriate to transfer a patient taking hormones to endocrinology when they present with pneumonia or a broken limb.

Morally, these are two quite different problems, but both share a view of the trans person as Other. Othering, whether as a unique class of complicated medical case or as a despised and stigmatized class of persons, makes it all too possible for providers to deny the patient in front of them.

We can de-Other for all but the most bigoted through a variety of means including acquaintance with persons perceived as Other, by resisting the sensation of Otherness and insisting on seeing the person as a person like us in the most important ways, and through medical education (implicit bias is notoriously resistant to deliberate change, but so far we are talking about explicit bias). Unfortunately, as Obedin-Maliver et al. found, medical education is woefully lacking in this respect: Of 150 medical schools which reported on curricular engagement of LGBT issues, the median time spent was 5 hours. 9 schools reported 0 hours pre-clinical training and 44 reported 0 hours of clinical. While 97% of schools discussed incorporating sexual behaviors in the patient interview, few discussed transgender issues at all. Of those which did, 1/3 discussed gender transition and 1/3 discussed sex reassignment surgery. There was no mention of teaching techniques for initiating or maintaining provider relationships with LGBT individuals. There was also no mention of the sort of preventive care transgender persons often need and which take general practitioners by surprise, for example that transgender men may still need to be screened for breast cancer, uterine cancer, or cervical cancer (PAP smears, etc.). I acknowledge that medical schools are under immense curricular pressure and face what must seem a zero-sum game, but lack of education on these issues is imposing serious damage on vulnerable classes of patients. Either medical education, continuing medical education (CME) on transgender health, or in-servicing such as the LGBT “cultural competency training” offered by the Veterans Administration must take up the slack.

Readers interested in this might consider taking a look at Joanne Herman’s Transgender Explained For Those Who Are Not. Herman is very clear that she does not speak uniformly for all transgender persons as there is great diversity within this group. However, she suggests several tips for talking with transgender persons which may be very helpful to providers. I give a few here that seem most applicable to provider-patient relations, and most likely to help providers avoid the sort of microaggressions which can be accidentally inflicted on transgender persons by well-intentioned clinical staff:

- If the person’s gender presentation is unclear or inconsistent, use the person’s first name instead of the pronouns he and she (Reiheld note: or gendered titles such as Mr., Ms. Etc.; and use the patient’s preferred pronoun or, if unclear, ask how the patient would like to be addressed)

- Don’t ask what the person’s prior name was

- Be aware that the person (may or) may not identify as gay. Gender identity and expression is not the same thing as sexual orientation.

- Be careful with the words you use: say “transgender” not “transgendered”; “transgender person” not “a transgender” or “a trans” or “a sex change” (Reiheld note: or anything that reduces the person to their trans status)

- If you desire a gender classification, ask yourself whether you really need it for this patient encounter or whether you simply expect it from the routines of daily interaction in our culture

- Reiheld addition: providers have been known to insist on using the person’s legal name, which may not be the name of choice, in the case of transgender persons, but then going to some lengths to note and remember a “normal” cisgender person’s preferred nickname. This gives rise to another tip: if the person introduces themselves, use the name they gave in interacting with them just as you would with anyone who expressed a naming preference.

- Reiheld addition: Remember the point I made above, namely that if you think you can’t treat the patient for care unrelated to trans status because of the fact that the person is transgender, this may not be the case or it may signal that you don’t know enough to know when you can and can’t treat. It then becomes critical to find out.

You can stir the buzz on bed with the use cialis prescriptions pharma-bi.com of sex toys, vibrators and other playful props. 3. A healthy free prescription viagra http://pharma-bi.com/category/analytics/visualization/ and happier lovemaking session is significant to flourish the relationship. First decide the team you are supporting and the player that draws your attention the most. canada viagra Kamagra magical medicine to over erection problems and enable best viagra for women you enjoy the love life to the fullest.

In addition to these tips which I compiled, the Transgender Law Center has compiled 10 Tips for Working with Transgender Patients.

These include tips on rewriting intake forms to include “chosen name” in addition to “legal name” as well as a third, blank option for “sex/gender” where the patient can more accurately describe themselves, as well as providing single-use restrooms which are not restricted to a particular kind of person (a version of making all restrooms accessible restrooms, a practice already common in clinics). These tips also urge providers to keep the focus on care rather than curiosity, and on sameness rather than difference (“treat transgender individuals as you would want to be treated”). Other tips have significant overlap with the list above, both Herman’s own points and my additions.

These tips are not meant to substitute for adequate medical education on transgender issues during pre-clinical and clinical programs. That has to come along and be part of patient-provider relations rather than part of a course of study in rare medical issues, and these tips won’t substitute for it. Nor will they make a dent in the behavior of providers with a deep personal commitment to the notion that transgender persons are Other and ought to be made Other. But for providers continue to value the patient-provider relationship and to treat it with care, who have had no medical education on these issues, and who are well-intentioned, these tips may be of some use.

Regardless, and here I borrow from a blog author who posted on the IJFAB blog last year, I urge providers to work out their attitudes to, and ways of interacting with, transgender patients before patient encounters rather than during patient encounters. The cost of denying the patient in front of you is not just that the particular encounter will go poorly. The cost of denying the patient in front of you is that patient’s perspective, from that point on, on seeking preventive and emergency medical care. The cost of denying the patient in front of you is their ability and willingness to take a risk on forming patient-provider relationships at all, with anyone. The cost of denying the patient in front of you is their health and well-being.

I look forward to reader comments, criticisms, and helpful emendations where I elided or failed utterly to account for some aspect of this issue.

—————————-

For those who would like to learn more about transgender persons and the wide variety of ways in which persons pursue what they see as their authentic selves, I recommend the National Center for Transgender Equality’s FAQ, “Understanding Transgender” and their handy single-page terminology sheet.