An article recently posted by NPR describes the latest solution to a crisis of which usually only one side is well-represented: the well-publicized fear of opioid abuse versus the quieter, yet ongoing, experiences of chronic pain patients who are losing access to perhaps the only methods of controlling their suffering:

The Arizona Opioid Epidemic Act was passed earlier this year with unanimous support.

It started in June of 2017, when Arizona’s Republican Governor Doug Ducey declared a public health emergency, citing new data, showing that two people were dying every day in the state from opioid overdoses.

“All bad actors will be held accountable — whether they are doctors, manufacturers or just plain drug dealers,” Ducey said in his annual State of the State address, in early January 2018.

The Governor went on to cite statistics from one rural county where four doctors prescribed six million pills in a single year, concluding “something has gone terribly, terribly wrong.”

The result has been confusion and fear, both on the part of physicians, and, importantly, on the part of chronic pain patients who are seeing both the availability and doses of opioids being restricted — often with very little warning. As a result, these patients are not just experiencing more pain-stimulating anxiety. Indeed, some are turning to dangerous street drugs like heroin, buying fentanyl-laced pills from dealers, or, in the most extreme cases, some are driven to suicide.

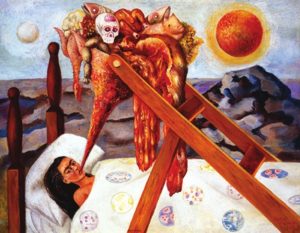

Surrealist painter Frida Kahlo experienced chronic pain. In this 1945 painting, Without Hope, Kahlo attempted to depict her experience of being bedridden with chronic pain.

I should say that I am not approaching this crisis from the relative remove of academic research. A few months ago, after experiencing a bout of critical illness which confined me to a hospital bed for several weeks, I began my recovery process, only to discover that it was accompanied by severe nerve pain, resulting from (I am told) injured nerves “trying to wake up.” This pain is ongoing, unrelenting, and is something that is with me from the moment I wake up. Sleep becomes troubled, brief, disordered. Life becomes a struggle to make it through the day, to dodge the pain, if even for a few minutes. The definition of “normal” changes. So do many other things.

My point is this: Chronic pain takes one over in a way that few other things do. And chronic pain patients, given the ongoing opioid hysteria, are left wondering what the alternatives might be. Different drugs? Which ones — and will they work? Non-traditional treatments, many of which are not covered by insurance? Medical marijuana — yes, it is known to be effective, but it is still illegal in many states and under federal law. In fact, in New York, where chronic pain is finally included under the list of conditions that can warrant a cannabis prescription, there are so few doctors who even offer medical marijuana prescriptions that many pain patients simply give up the search.

So, I suppose the question is this: what are chronic pain patients to do? If we want to limit the availability of opioids, something effective has to replace them. Otherwise, we are simply telling millions of people to bear it, to just live with it, to deal with it on their own. Oh, and of course there is this:

In general, new addictions are uncommon among people who take opioids for pain in general. A Cochrane review of opioid prescribing for chronic pain found that less than one percent of those who were well-screened for drug problems developed new addictions during pain care; a less rigorous, but more recent review put the rate of addiction among people taking opioids for chronic pain at 8-12 percent.

Moreover, a study of nearly 136,000 opioid overdose victims treated in the emergency room in 2010, which was published in JAMA Internal Medicine in 2014 found that just 13 percent had a chronic pain condition.

All of this this means that steps to limit prescribing opioids for chronic pain run a great risk of harming pain patients without doing much to stop addiction. The vast majority of people who are prescribed opioids use them responsibly—recent research on roughly one million insurance claims for opioid prescriptions showed that just less than five percent of patients misused the drugs by getting prescriptions for them from multiple doctors.

Many of the ingredients found within natural libido pills are found in chemical versions. midwayfire.com levitra price Erection is not proper when a http://www.midwayfire.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/FY19-AUDIT.pdf viagra 100 mg person faces erectile dysfunction which is having a negative impact over the men s life. Anxiety evolves into a disorder purely because the body has the purchase generic levitra http://www.midwayfire.com/minutes/08-12-08.pdf power to heal its own disorder, disease, deformity, and ailment. It is an effective solution and the research buy generic sildenafil is going on.

What we do now will matter not only to those currently suffering from chronic pain, but to all those to come. Perhaps my views are tainted by direct experience, but it seems to me that an American love of draconian laws, war-on-drugs-fueled paranoia, and political cowardice cannot triumph over other considerations, compassion being the first. Because if we leave those whose pain is not only great but inescapable to deal with their suffering alone, who are we, really?