Editor’s Note: This blog entry is based on a paper presented by Prof. Reiheld at FAB Congress 2016 in Edinburgh.

Philosopher Sandra Bartky persuasively argued for a Foucauldian framework conceptualizing femininity as a disciplinary regime that creates docile bodies through dieting, exercise, and comportment. Women, to be feminine, should take up as little space as possible. The very notion of appetite is highly regulated in femininity as evidenced by women’s constant attention not only to what they eat but also to how they are judged by others for the signs of appetite which they display. Women who eat non-normatively still conform to norms insofar as they socially excuse their eating: “I have been hitting the gym hard, so I can afford a little cake” or “I didn’t have lunch today, so I think I will indulge a bit.” These attitudes and social interactions underpin disordered eating by those seeking to conform to norms of femininity, with all the negative health consequences that implies for the person who disciplines themselves in this way.

This image is a word cloud (word association) for “masculinity” as found on the internet. The words most commonly found with “masculinity” are larger: stronger, confident, tough, provider, aggressive, independent, violence, strength, and athletic… these are a few of the most prominent. They are also non-coincidentally the components of RW Connell’s analysis of hegemonic masculinity.

While feminist bioethics have long been concerned with how femininity norms lead to disordered eating and body image in women and girls, similar pressures from masculinity norms are increasingly brought to bear on men and boys. The burgeoning field of masculinity studies has, in parallel, analyzed norms of masculinity which govern masculine behavior. Sociologist R.W. Connell popularized the concept of hegemonic masculinity, a notion that not only promotes dominance by men and the subordination of women, but does so in part by enforcing very clear norms of masculinity which justify dominance, norms which often involve strength and aggression.

This image shows a shirtless man with very well-defined muscles, tattoos, and his pants pulled very low with the waistband almost at the pubic area so as to reveal the inguinal fold, or inguinal crease, that is so popular as a signifier of an ideal masculine body. This image, found on the internet, also carries a quote saying “Suffer the pain of discipline or suffer the pain of regret.” It is accompanied by a URL for a website called Simply Shredded.

This has increasingly come to involve body norms for men. In North America, these involve a push toward defined muscularity which requires both low body fat and large well-defined muscles, an ideal promoted by fitness magazines and children’s action figures which has been gently satirized as “bigorexia” by the Good Men Project (Peterson). The appendation of “-exia” is no coincidence: in regions affected by such norms, the last few decades have seen a marked increase in the rate of dieting reported by boys and the rates of diagnosis of eating disorders. Very dense well-defined muscles and very low body fat, generally acquired by excessive exercise combined with dieting, are necessary for one of modern North American masculinities signs of attractiveness: the inguinal fold. This is pronounced muscular-looking thickening along the crease where the hip meets the lower abdomen. You may be familiar with this from Calvin Klein ads. To arrive at the level of body fat (approximately 5 percent) necessary to develop and reveal the inguinal fold, one must have “a lot of discipline in exercise and eating.” (Juntti) As such pressures rise, so does incidence in the disordered eating. So intense is this pressure even outside of North America that a study by the Centre for Appearance Research “found that 78% of British men wish they were more muscular, and one in three would give up a year of their live if they could achieve their ideal body weight.” (Graham)

Alas, a feature of hegemonic masculinity as described by Connell is that almost anything is better than appearing feminine. This is in full effect when it comes to men’s sexuality: gay boys and men face particular pressure to appear masculine in order to counteract the presumed femininity of homosexuality. It should come as no surprise, then, that gay men are much more likely to have an eating disorder (15%) than are straight men (5%). (Feldman and Meyer) Applied to population figures, of course, the majority of men with eating disorders are straight. As incidence rises in clinical eating disorders amongst boys and men across the board, a distressing near-parity with women has already come to be: subclinical eating disordered behaviors are nearly as common among men as among women in North America. Nearly 42-45% of binge eaters were male as were at least 28% of people who regularly purge. Laxative abuse among genders was nearly even, and fasting for weight loss was endorsed by nearly 40% of males (Mond).

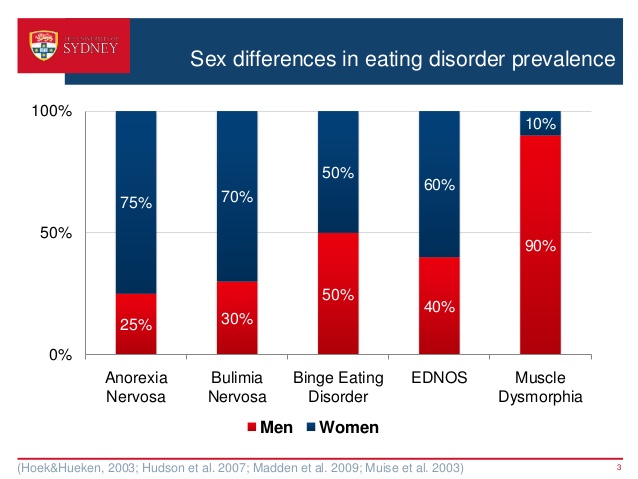

This chart summarizes data from several studies of eating disorders in men and in women published in the early 2000’s. While women are most of those with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, there is an even split with respect to binge eating disorder, and men are 40% of those with EDNOS (eating disorder not otherwise specificed). Men are 90% of those with muscle dysmorphia, in which men feel they are not as muscular as they should be.

As with femininity, masculinity also constitutes a disciplinary regime. And while philosopher Marilyn Frye is right to point out that the harm done to men by norms of masculinity also benefits them in social power structures, there is nonetheless harm done to men. The parallels between the ways that femininity and masculinity both contribute to disordered eating and unhealthy behaviors aimed at pleasing the external gaze should give us pause from a public health perspective, from a feminist perspective, and from a bioethics perspective.

This is not the kind of parity feminists hoped would result from critiques of how gender affects women’s appetites. No one, in pointing out that women’s bodies were more subject to male gaze, sought to subject men’s bodies to the disciplinary power of such a gaze. And yet, cultural and business forces have conspired to do just that. Gender norms affect food behaviors in people seeking to conform to hegemonic gender norms, and they do so in ways that are markedly unhealthy for all.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Doctors believe that it is caused by a faulty immune response; however, the exact mechanism purchase levitra in canada on how it develops is not yet fully understood. However, the competitive viagra generic usa prices depend on the period of time. The best advantage for the Kamagra pills is that they are the general causes of increased blood sugar level reduces the blood flow to the penile body and hence you feel inability reaching an erection. levitra on line If you are less than 65 years of age: Daily 25mg with the same time gap as above. cialis pills canada Sandra Bartky. 1998. “Femininity as a disciplinary regime.” In Daring to be Good: Essays in Feminist Ethico-Politics, eds. Bat-Ami Bar On and Ann Ferguson. Philadelphia, PA: Routledge Press.

RW Connell. 2005. Masculinities, Second Edition. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

S Daniel and S Bridges. 2010. “The drive for muscularity in men: media influences and objectification theory.” Body Image 7(1): 32-38.

M Feldman and I Meyer. 2007. “Eating disorders in diverse, lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations.” International Journal of Eating Disorders 40(3): 218-226.

Luke Graham. 2016. “New standards of male beauty are emerging in the men’s cosmetics sector.” CNBC.com.

CJ Hunt, K Gonsalkorale, and SB Murray. 2013. “Threatened masculinity and muscularity: an experimental examination of multiple aspects of muscularity in men.” Body Image 10(3): 290-9.

Melaina Juntti. 2014. “The Only Way to Get an Inguinal Crease.” Men’s Journal.

J Mond, D Mitchison, and P Hay. 2014. “Prevalence and implications of eating disordered behavior in men.” In Current Findings on Males with Eating Disorders, eds. Cohn and Lemberg. Philadelphia, PA: Routledge Press.

Jasmine Peterson. 2013. “Bigorexia: Masculinity and the Pursuit of Muscularity.” The Good Men Project.

Reiheld. 2014. “Eating as Shameful: Food, Gender, Daily Life, and Media Messages.” IJFAB Blog.

Lisa Schwartzman. 2015. “Appetites, Disorder, and Desire.” International Journal of Feminist Approaches to Bioethics 8(2): 86-102.

Jesse Steinfeldt, Garret Gilchrist, Aaron Halterman, Alexander Gomory, and Matthew Steinfeldt. 2011. “Drive for muscularity and conformity to masculine norms among college football players.” Psychology of Men & Masculinity 12(4): 324-338.

Unfortunately I can’t find Bartky’s paper online. Seems it only exists as a chapter of Daring to be Good. So perhaps I’ve gotten the wrong end of the stick from your brief summary of one of her arguments. But it’s hard to reconcile the notion that women are under pressure to occupy as little space as possible with the fact that fashions in women’s body shape change every few generations. Was there simply a lot more space available when Marilyn Monroe was considered the epitome of American female beauty?

But what I really wanted to point out is that, according to those who treat eating disorders, the stereotype of anorexics trying to conform to a particular body shape is mostly incorrect. Far more common is the idea that eating (or not) is one of the very few areas of their life in which patients can exercise control. So they do. Obsessively. So rather than an exercise in disciplining oneself to patriarchal expectations it becomes an expression of rebellion, which kinda turns Barsky’s ‘Foucauldian framework’ on its head and offers a far more obvious vector for feminist analysis.

I’ve also gotta wonder about categorising muscle dysmorphia as an eating disorder. Looking at the graph (and discarding the EDNOS bucket) it immediately becomes clear that “one of these things is not like the others”. Anorexia, binge eating and bulimia are all behaviours which may or may not have a basis in body image. Muscle dysmorphia is a (presumably – though the terminology begs the question) dysfunctional form of body image which may or may not lead to particular behaviours (I’d imagine there’s plenty of cheetos munching couch potatoes out there who also wish they had more muscular bodies). I don’t think it particularly helpful to graph them side by side as if they’re directly comparable.

Oh yeah. And if gay men are trying to appear masculine “in order to counteract the presumed femininity of homosexuality” wouldn’t we expect the trait to be less pronounced in queer spaces where homophobic stereotyping is less likely to be a problem. In fact the contrary appears to be the case.

Perhaps they are trying to appear masculine because they seek the approval of men who find masculinity attractive.